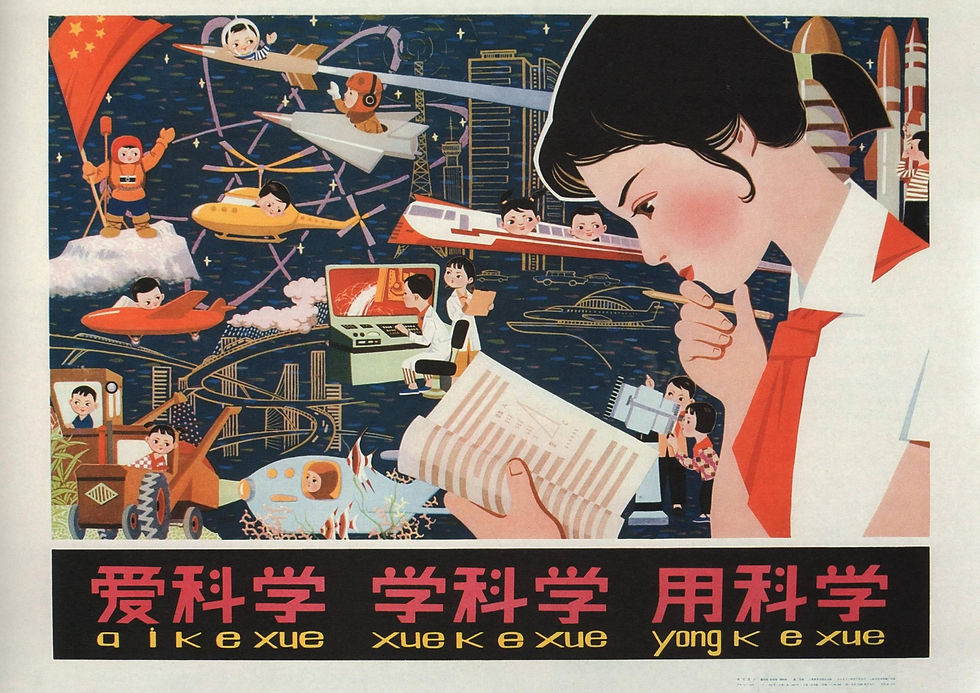

Image: Chinese poster from the 1980s promoting science. Caption translates to "love science, learn science, use science".

I loved hearing about how Prof Firestein came to create a course called “Ignorance”, regarding what we don’t know about science. It is fascinating to heard about his perception of gap between the way scientists pursue science and the way they teach it, quote: “we don’t care about we know, we care about what we don’t know.”

What are the stakes of this with regards to prediction and uncertainty? Prof Goodman went on synthesised Firestein’s sentiment into a broader theme: (quote) ‘Most people just want to know what they can know about things they know nothing about”. This chain of ideas is undeniably important in terms of how science is communicated. In terms of public science, we might focus first on what information people want to know, before we were even thinking about how to communicate it. But the point that Prof Firestein makes is that some of the most interesting and rewarding pathways of scientific knowledge are embodied by the unknown. So what does it mean to disseminate scientific information that is contingently unknown? How can we truly embrace ignorance in a productive, educative sense?

This dialectal project, which practically involves ‘producing’ ignorance in a way that is is generative. On some level our ‘innate sense of time’ and its relationship to progress is highly dictated by our sociocultural fabric, which leads me to think that an intellectual history or historiographical approach could be a fruitful way to explore our relationship to scientific futures.

Studying techno-cultural events such as the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution in China, for example, where scientific technology was fundamentally intertwined with conceptions of statehood, empowering individual action, and crucially scientific futures, can enrich our own conceptions of what could be done in terms of communicating science in a way that is not only informative, but also cultural. Seeing what went wrong with projects such as these is an invaluable opportunity when we’re answering these sorts of questions, but also witnessing the urgency and risk-taking that states will employ to disseminate scientific information when it is related to ideas of ‘progress’ or ‘prestige’.

It leads me to pose these questions: What are the sociopolitical triggers that lead scientific knowledge to deeply permeate public consiousness? What would it take to re-invigorate the close allyship of scientific attainment and conceptions progress and prestige not just in the realm of policy-making, but also in the realm of the individual?

Hi Lauren! I must say, I LOVE how you set up and posed this question. Further, the question itself is extremely arresting. The closest answer I can come up with is that much of modern society has just expected us to advance scientifically, and so we don't take much pride in whatever advancements we achieve. For the United States, I think after we "won" the space race, the appreciation for new scientific discoveries decreased, as nothing seemingly would ever be as culturally significant or transcending. Even more recently, with the viral picture of a black hole, the awe surrounding that image was only temporary. In an age where so many people, especially children, are surrounded by the products of scientific advancement, said advancements have become expected, and so the appreciation of them is virtually non-existent. Again, I honestly REALLY like this question, and I'm sure there are more well-developed answers or solutions out there. I hope that mine suffices :)